Imagine a world where getting straight A’s, and having a 4.0 GPA, is neither extraordinary nor even an especially grand reason to celebrate.

This is quickly becoming the reality at schools ranging from Yale University to local public schools in our area to Saint Stephen’s Episcopal School. According to the New York Times, schools across the country are currently suffering from a “grade inflation” (more A’s for more people), diminishing what it means to meet the high standard and incredible achievement.

In the groundbreaking Times piece Nearly Everyone Gets A’s at Yale. Does That Cheapen the Grade?, the author Amelia Nierenberg discusses the increase in A’s being handed out at universities.

The Times conducted a study and found that “At Harvard, 79 percent of all grades given to undergraduates in the 2020-21 year were also A’s or A minuses. A decade earlier, that figure was 60 percent. In 2020-21, the average G.P.A. was 3.8, compared to 3.41 in 2002-3.”

This same study also found that at Yale University, the mean grade point average was a 3.7 out of a 4.0, showing an increase from pre-pandemic years.

And when it comes to high schools, the inflation doesn’t seem to be very different. According to a 2023 Forbes education story, “In 2022, more than 89% of high schoolers received an A or a B in math, English, social studies, and science.”

Although seeing an abundance of A’s may seem like a good achievement, it certainly is not a sign that students are “getting better.” If the majority of students receive A’s, does that mean that we’re all getting smarter, or that the bar is getting lower?

Likely, it’s the latter. Not only does grade inflation take away the value of the once-hard-earned letter, but it makes students indistinguishable, and it makes excellent students seem ordinary.

Receiving all A’s should signify excellence, and the feat should be something rare, not ordinary and unappreciated. Standing out as a student, especially a high school student, feels impossible to achieve at this point, since getting straight As is no longer a distinguishing feature.

The situation with grade inflation certainly doesn’t mean that we should stop giving well-earned A’s at all. Instead, schools should remind themselves of the standard and reinforce it.

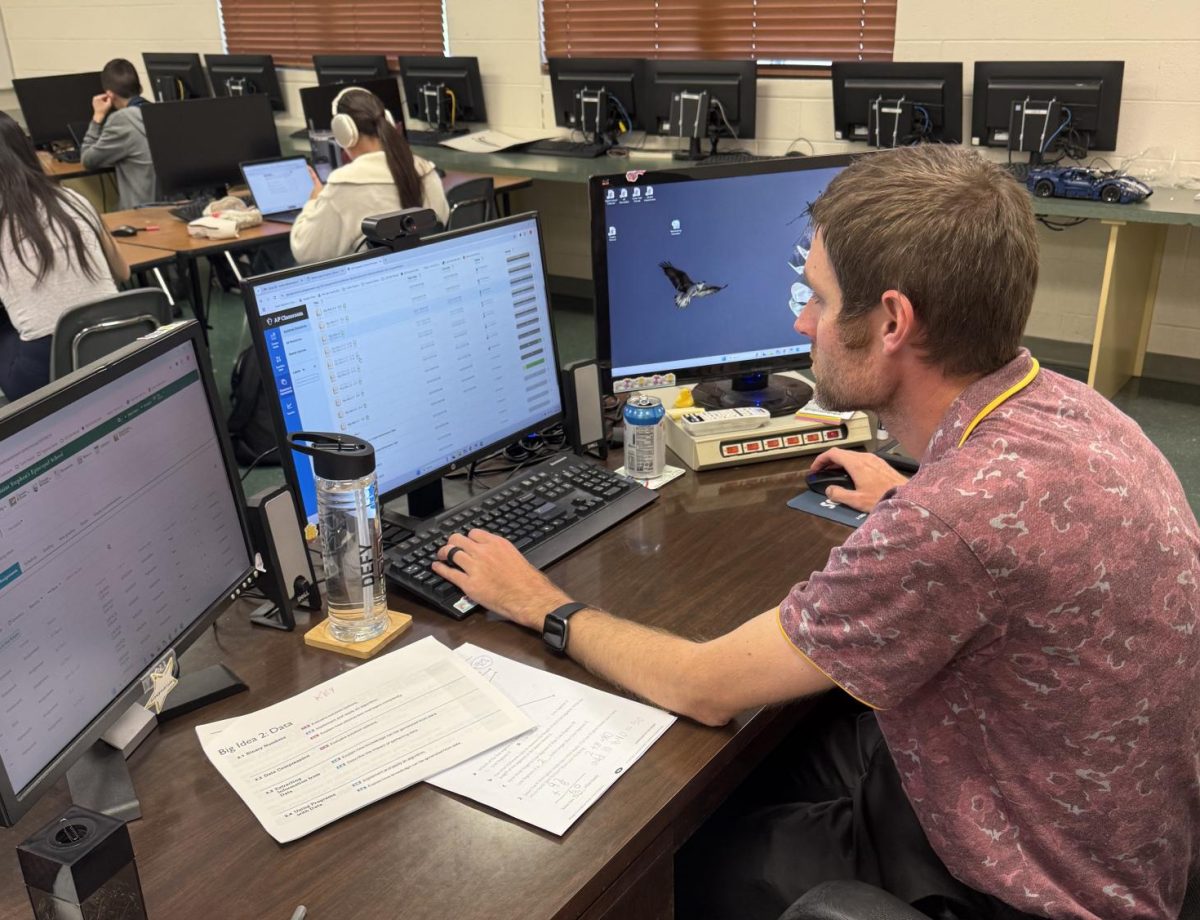

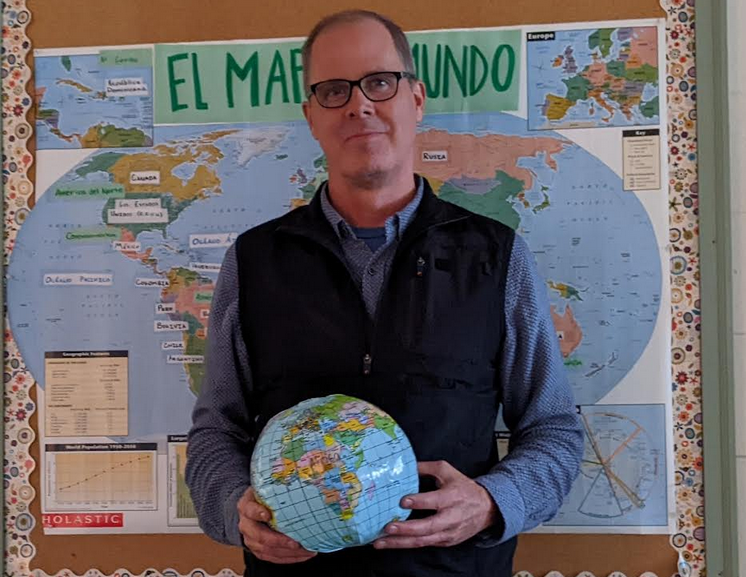

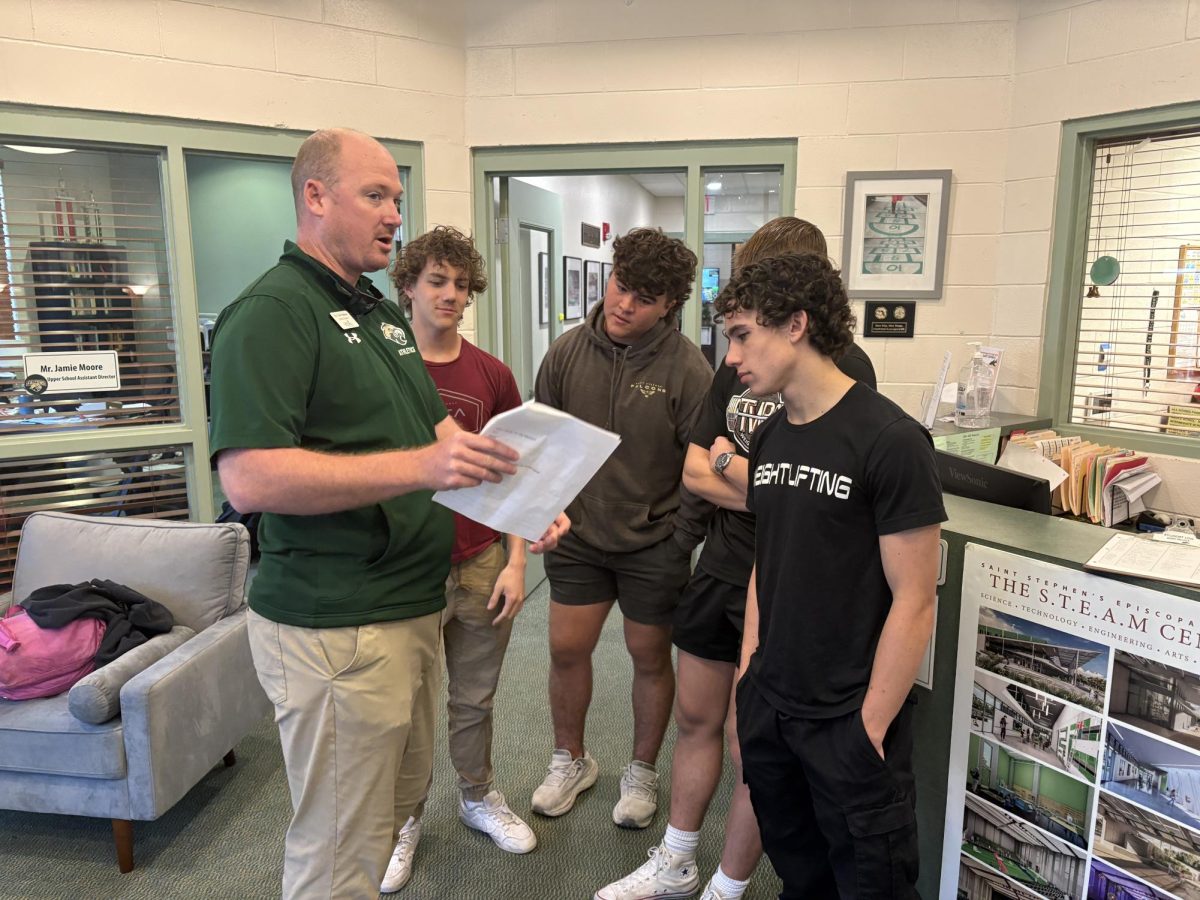

Yale graduate and Saint Stephen’s History Department Chair, Mr. Patrick Whelan, shed some light on the origin of grade inflation, which started in the 1960s.

“At that time, male college students who were earning poor grades were often drafted into the military to fight in Vietnam,” Whelan said. “College professors who did not want to send their students to the Vietnam War did what they could with the grading scale to make sure that students would not drop out and be drafted.”

Whelan’s claim is supported by a story in The Harvard Crimson from 2016 entitled LBJ Wants Your GPA: The Vietnam Exam. In the piece, the author explains the effect of the draft on educational institutions and the question of professionalism and fair grading when the consequences are greater than a failed test.

As time progressed in later decades, so did grade inflation. Mr. Whelan wondered how it feels for certain students who struggle with perfectionism, students who desire to get an A on everything, believing that earning any grade lower than an A is unacceptable.

Mr. Whelan enforced his idea that “grading should reflect learning” in his classroom, especially for his Advanced Placement History students, who earn what they would earn if they were “taking the same course as a freshman at a highly competitive college or university.”

Even with the high bar set in Mr.Whelan’s classroom, he said he takes pride and credit for the fact that many of those students end up receiving grades of A and A-.

But, Mr. Whelan’s students very rarely will ever receive an A+.

“I also believe that grades of A+ should be very rare,” Whelan said.

Director of Research and Curriculum Mrs. Christina Pommer shared that in her view, grade inflation is nothing new.

“As someone who did really well in school, I know that my friends and I pushed each other to get straight A’s,” Pommer said, “and I remember that we often talked more about the grade itself than about the material or what it took for us to earn those grades. So while there might be increased inflation, this isn’t something that is new.”

Pommer states the belief of how students who truly grasp the material well can earn an A for their work.

Knowing grade inflation is on the rise, it begs the question: Are Saint Stephen’s students also seeing the depreciation of what it means to get an A at their own school? Is our school, and high schools like us with students all trying to get into college, giving out too many A’s?

The answer? Probably yes. But is this impacting kids as they yearn to get into colleges?

Director of College Counseling Mrs. Tricia Hasbrouck has a different view on the idea of grade inflation and she wonders if it’s truly affecting students’ ability to get into colleges.

Hasbrouck explained that when a student applies to a college, a “profile” goes with them, explaining the grading system of the school, since some high schools operate on a scale other than a 4.0 measurement. From here, colleges tend to recalculate the school-given GPA into their own evaluation system.

The solution to this issue doesn’t mean that to earn an A on everything, students should go to extremes and drain themselves. This also doesn’t mean that a limit should be put on the number of A’s given, which Princeton University tried in the 2010’s to combat grade inflation. They eventually reversed the decision because it was creating an overly competitive atmosphere.

Perhaps the biggest problems with ”easy A’s” are that they signal to students that they don’t need to work hard to succeed, they give parents a false sense of how their kids are doing, and they allow students to graduate without essential knowledge or skills. They also undermine learning, as Brown University researchers reported that students appear to learn more from teachers who are tough graders.

Stuart Rojstaczer, a retired professor at Duke, claims that grades are like a currency. They increase over time, and just like when there’s economic inflation, the greater the inflation, the more value is lost. It works the same for grades as it does money.

So what’s to be done about this? How should we view this rising in grades across institutions, and what should we do? (Conclude with your thoughts?)

Not only does this inflation of A’s result in a sense of averageness when the once-coveted grade is achieved, but it enforces pressure on students to distinguish themselves outside the classroom since they can’t inside the classroom. As the New York Times article points out, the rise of A’s makes extracurricular activities and personal hobbies feel stressful and frustrating, rather than relaxing and fun like they’re supposed to feel.